Most Zimbabweans are living in extreme poverty, and state services like health and education are now virtually defunct. The grim reality emerges as Viktor Posudnevsky talks to one woman who is struggling to survive in Harare

It’s hard to get through to Zimbabwe’s capital by phone; regular power blackouts mean that people go for days without access to communications or electricity – not even a lamp to read, write and study. I succeed in getting through to Joyce on the second day of trying.

Joyce, a 42-year-old primary school teacher in Harare, asks me not to reveal her surname as it might endanger her livelihood, which is quite bleak as it is.

“Wait a minute,” she says after I introduce myself. There is a brief silence as she checks the doors and windows (as she tells me later). “If they hear me talk politics to an outsider I may disappear,” she explains. “And my family won’t know what happened to me”.

Plain-clothes secret policemen are rumoured to ‘haunt’ the streets of Harare at night, listening in to private conversations and keeping an eye out for suspicious activities. Zimbabweans hold no illusions about their fate should they be caught. Nearly everyone knows someone whose friends or family ‘disappeared’ in the middle of the night. Some of these people were taken to a dreaded place called Goromonzi, a notorious torture camp which has become a familiar haunt for members of the political opposition.

“Today me and my friends discussed some of the political issues in my house,” says Joyce. “We always go to a safe room, and I make sure that all the doors and windows are closed. If somebody we don’t know well comes in we start praying and singing, as if we gathered there to worship.”

Of late, abductions, beatings and torture have become commonplace in Zimbabwe. The people understand this can happen to anyone, and are afraid. Even in a remote place like Ireland, Zimbabweans are paranoid. As one Zimbabwean living here who wished to remain anonymous tells me, there are rumours in the community as to who might be a ‘spy’ for the Zimbabwean government.

But the threat for those living in Harare is much more real. “There was a councillor in my area who used to talk openly about politics in shops and public places,” Joyce tells me. “Then one night he just disappeared. The police took him to a torture camp. When he returned he was badly beaten and crippled. He soon left for South Africa – it was not safe for him to stay here.”

‘The money is not enough’

When you listen to Joyce’s stories, you begin to understand why the government is so hard on its own people. The situation in the country is such that terrorising the population is the only means to keep it under control.

Joyce and her family are only able to survive because her sister lives and works in Ireland. Every month she sends money back to Zimbabwe.

“I am a teacher and the salary is 17 trillion [Zimbabwean] dollars,” ex-plains Joyce. “But at the moment nobody is getting more than 2 trillion dollars per week from the government. The governor was on TV recently and he said that the state cannot afford to pay more than that.”

Two trillion dollars is less than 10 US dollars, and a loaf of bread in Harare costs one tenth of that. “The shops are not empty as they used to be before. But very few people can now afford to buy anything in them. The money is just not enough,” says Joyce.

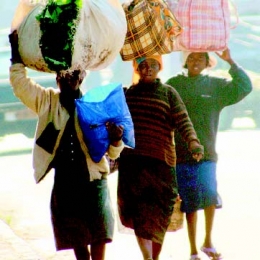

Zimbabweans are often forced to go abroad – to South Africa or Botswana – in order to buy groceries as they are cheaper and more widely available. Joyce makes the trip nearly every month. The journey from Harare and back takes a day and a half. She leaves early in the morning and comes back late the following night.

But the life of those who don’t have families abroad is much worse. It is estimated that up to a half of the Zimbabwean population survives on donations from charities. “Many poor people also work in the fields for food and shelter,” she says.

Would Joyce go abroad like her sister if she had an opportunity? There is a pause. “Yes,” she says finally. “The situation is such that you have to leave Zimbabwe if you are presented with the opportunity. What kind of life is this when your children cannot go to school and cannot go to hospital in case they get sick?”

She says the Zimbabwean government keeps postponing the date when state schools are to reopen for the new year. “At first they said 20 January, now it’s 12 February... As far as I’m concerned the schools might never reopen because the government just doesn’t have the funds to run them.”

Some schools are functioning, but the parents have to shell out large amounts of money for their children to attend. Only a select few can afford this. It is even worse with hospitals.

“To go to a hospital you have to pay 10 US dollars for a medical card and then pay for medication,” Joyce says. “Most people cannot afford this and some are just dying at home.”

Because of the recent cholera outbreak in the country, Unicef distributes water purifying tablets for free, but not everyone gets them. What often happens is that people who do get the tablets sell them on to those that don’t for 2 trillion dollars per pill. “One tablet is only enough to purify about 20 litres of water,” says Joyce. “For a family it will last for three to four days only. Most people can’t pay so much and just drink tap water.”

But even in the worst of times some good things are bound to occur, and I ask Joyce what positive developments she has seen in recent years. She comes up with three.

“There is freedom of movement – something that we didn’t have before,” she says. “If you’re not anti-government you can freely move up and down the country. You can also worship freely and go to any church you like, unless you go there to talk politics.”

She also says the police has become more “understanding” towards the population. “Previously if they saw somebody, say, selling petrol in the street, they could just shoot that person without thinking or asking anyone’s permission. Now they can still do that, but I hear more and more stories when they just leave the person be. They see that the situation is bad and understand that people have to make a living.”

If the situation is so bad, why don’t people revolt?

“We are powerless,” says Joyce. “Nobody here has guns apart from police, army and war veterans. Armed police can easily overpower any protest.

“The people are very angry at the situation, but there is not much they can do. They have got nothing to defend themselves with – this is the only thing that deters people from acting.”

She says Morgan Tsvangirai and his Movement for Democratic Change have support from the people, but the government “is not talking seriously” with the opposition.

“Realistically I believe the only thing that can change the situation is a war,” she says. “And I am looking forward to a war if it is the only way out.”