Concluding his account of his recent visit to India, Charles Laffiteau comes into contact with some of the country’s greatest riches - and the poorest of the poor

As I was leaving the Gandhi Museum to return to my hotel, a young girl of maybe 13 years approached my car, begging for money. She was obviously poor and homeless, dragging a very deformed foot around on crutches, and looked like she hadn’t had a bath in at least a week. The sight of this pitiful young waif was more than I could bear, so I reached into my pocket and gave her 10 rupees (about 15c).

The look of absolute joy and gratitude on her face when I dropped the coins into her dirty palm was indescribable, and judging by her reaction you would have thought I had just given her a million euro.

I responded by grabbing my camera to take her picture, and as soon as she saw the lens she became even more animated, smiling and waving at me while she thanked me again and again, until my car slowly pulled away into traffic. I didn’t really need a photo, because as I write this I can still see her smiling face pressed against my car window.

The next day I went to visit Akshardham, a Hindu temple which is as modern a tourist attraction as all the others sites I visited in India are ancient. But unlike the older and much more historic holy places the country is famous for, visitors to Akshardham must check in their purses, phones, cameras and other valuables before they are even allowed to enter the temple’s grounds, in part to ensure that no photos are taken inside.

Within the temple complex, one finds beautifully manicured gardens dedicated to famous Hindus important to Indian history, as well as exhibitions which explain the Swaminaran faith and Hindu teachings, along with gold and marble statues of various Hindu deities. For a fee of 50 to 100 rupees (75c–€1.50) there is an indoor boat ride, a huge new Imax theatre showing a movie about Lord Swaminarayan, and a sound and light show which depicts the Hindu vision of the beginning and the end of the world. But compared to all the other places I saw in India, Akshardham did strike me as a bit over the top.

A few days later, while I was being driven back to my hotel from Jawaharlal Nehru University, I had another memorable encounter with the poorest of India’s poor; a rather sad looking little five-year-old boy dressed in rags and caring for his year-old baby brother. But when I stopped to take his picture, he stood up smiling and waved happily at me as if he didn’t have a care in the world. When I gave him 10 rupees, he let out a whoop as if he had hit the jackpot, and the two of them began following my rickshaw as we moved along with the flow of the traffic.

Once again I didn’t really need a picture of him and his little brother to preserve the memory, because it is still as fresh in my mind now as it was right after I lost sight of them in New Delhi’s traffic congestion. I am still amazed at how genuinely happy India’s poorest people and children appear to be. Indeed, money can’t buy that kind of happiness.

The following weekend I went to India Gate and the beautiful government buildings that house India’s parliament and the prime minister’s offices. It’s an area of New Delhi curiously devoid of the squalor one sees everywhere else in the city.

That weekend also saw me walking the grounds surrounding Qutb Minar, one of the largest minarets in the world. This prayer tower was once part of one of the largest mosques in the world, Quwwat al Islam Mosque (The Power of Islam Mosque), which now lies in ruins. Ironically, the mosque was originally constructed using the ruins of older temples built for the Hindu and Jain religious faiths, so what remains today is a diverse mix of India’s Hindu and Muslim architecture. The site also holds the graves of some of India’s ancient rulers and a huge iron pillar, which never rusts, that was taken from a Hindu temple.

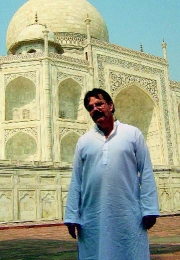

For my final few free days in New Delhi, I took an overnight trip to Agra to tour one of the modern-day wonders of the world, the famous Muslim shrine to a man’s love for his wife, the Taj Mahal.

To help protect the beauty of this white marble masterpiece from pollution, petrol burning cars and trucks are banned from the area surrounding the building, which upon closer inspection is actually white marble with calligraphy panels made of inlaid jasper.

Inside the mausoleum is the tomb of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan’s favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal, surrounded by beautiful and intricate geometric designs made up of inlaid lapis and other semi-precious stones.

The entire Taj Mahal complex is actually a series of towers and buildings that are surrounded by and connected to beautifully designed and well maintained gardens. It would be safe to say it would cost trillions of euro to build a complex like this today.

As I was leaving Agra to return to New Delhi and my flight back to Ireland, I had one more memorable encounter, this time with a native Indian woman carrying a months-old baby. She was begging for money, and I once again parted with 10 rupees. And just like the children before, she was overjoyed and thankful while I took her photo.

Today I am a much richer person because of what I experienced in India. I believe that India’s real jewel isn’t the Taj Mahal or any of its magnificent temples and ruins – it’s India’s people. The vast majority of Indians may be extremely poor in terms of material possessions, but they are incredibly rich in character and spirit.

Charles Laffiteau is a lifelong US Republican from Dallas, Texas who is currently pursuing a PhD research programme in Environmental Studies at Dublin City University