Taking a glance at the figures, and one might expect South Africa to be more like the Wild West than one of Africa’s most successful nations.

Crime – especially violent crime – seems to be out of control. The South African Police Service has reported a murder rate of 38.6 homicides for every 100,000 South Africans, one of the highest in the world.

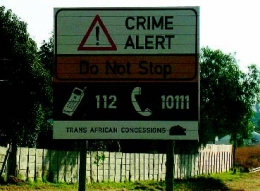

In 2007, there were 75.6 rapes per 100,000 people, and car hijackings are such a persistent problem that signs have been erected on roadside to warn motorists when they are entering a ‘hijacking hot spot’.

“The amount of crime incidents isn’t the biggest problem, but the violent nature thereof, which is mostly alcohol-related and happens in non-tourist areas,” says Malan Jacobs, a South African and founder of truecrimeexpo.ca.za.

In South Africa, like everywhere else in the world, crime is most closely linked to poverty, and the ‘rainbow nation’ certainly has its share. With an unemployment rate of 24 per cent by conservative estimates, many South Africans live below the poverty line and – not surprisingly – most crime is committed amongst the poorest, without affecting the majority of wealthy South Africans or tourists.

“There are places which are much safer than parts in European countries. Thus, it always in my opinion depends on the where in South Africa, rather than just ‘South Africa is an unsafe country,’” says Jacobs.

Many are quick to draw a connection between the poverty of the South African townships and the days of apartheid. But poverty based simply on discrimination isn’t the only root of South Africa’s crime problem.

“I cannot blame apartheid for crime,” says Bishop Winston Pienaar of the Restoration Life Ministry in Cape Town. “After apartheid, when we became a democracy, there’s a learning curve in how a democratic society handles crime. Some people, including politicians, lost control. But we cannot simply blame apartheid for committing crimes.”

Yet undeniably, the lack of an appropriate police force immediately after apartheid coupled with the depravation of the townships to fuel a criminal problem that has grown only stronger over the years. Many white South Africans left the force, leaving the police understaffed and under-experienced to handle an escalating situation.

But times appear to be changing. Crime has been named one of the top five priorities of the new Zuma administration, and the training of thousands of new police recruits seems to be stemming the tide of crime, and even turning it back.

“One of the things I’m really positive about is that crime is getting under control right now,” says Bishop Pienaar. “Now, in areas where police were almost never seen, there is now a visible presence. I’m not saying we are not having [crime], but I am saying that we are managing it.”

And the numbers, still grim as they may be, seem to support Pienaar’s observations. Since 2001, the murder rate in South Africa has fallen by about 10 homicides per 100,000, and rapes have fallen by around 17 per 100,000. It’s slow progress, but progress nonetheless.

At the same time, tourism is thriving as visitors are undeterred by crime reports, and with the World Cup less than a year away, security in South Africa is at an all time high.

“One thing that does concern me is unemployment,” adds the bishop. “You cannot have a country with an unemployment situation of 44 per cent. This will definitely mean more crime if it is not dealt with. But I’m positive we can stem the tide.”

Private security: a growing industry

In reaction to high crime rates and an understaffed police force, many South Africans have turned to private security firms for extra protection.

Firms all over the country offer a wide variety of services such as CCTV, electric fencing, security systems, foot patrols and private guards, many of whom are armed.

“Clients look for the protection of assets and their people, plain and simple,” says Theo Vermaak of Sirius Risk Management, a security company based in Gauteng.

But while most firms operate strictly within the law, others have been accused of operating as vigilante groups, doling out beatings and intimidation to criminals and suspected criminals.

“It’s not necessarily the norm, but let me put it this way: you do find people who prefer that type of service,” says Vermaak. “But again, I can’t say that’s the norm.”

One such firm, Mapogo, was profiled Louis Theroux in his Law and Order: Johannesburg special. In the programme, members of Mapogo openly admit beating people they claim to have caught stealing.

Those who support the use of such tactics argue that because the police force is overburdened with crime, it is up to private firms to administer justice in such a fashion. It’s a sentiment not echoed by most South Africans.

“Private security cannot act as a police force,” says Vermaak, “but you can act as a deterrent to crime and support the police. At Sirius, we work with the police to help people stay safe.”