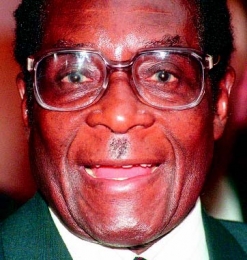

Robert Mugabe has left an appalling legacy in Africa. But he’s not the only one. So why is the Zimbabwean leader demonised by the west as a dictator beyond all others, asks Gearóid Ó Colmáin

‘This Hitler has only one objective: justice for his people, sovereignty for his people, recognition of the independence of his people and their rights over their res-ources. If that is Hitler, then let me be a Hitler ten-fold.” So said Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe in 2003.

‘This Hitler has only one objective: justice for his people, sovereignty for his people, recognition of the independence of his people and their rights over their res-ources. If that is Hitler, then let me be a Hitler ten-fold.” So said Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe in 2003.

Critics on both sides of the left-right paradigm generally agree on the appalling legacy of Mugabe’s rule of Zim-babwe. Unsurprisingly, the mainstream media beams apocalyptic images of hunger, devastation and disease as the Zimbabwean economy continues to collapse.

But the origins, as well as the internal and external forces which have contributed to this catastrophe, are rarely discussed in detail. Instead, Mugabe is represented as the epitome of the post-colonial corrupt African leader, opp-ressing his own people in an insane attempt to preserve his brutal autocracy.

Currently ranked as number 7 on Parade magazine’s World’s Worst Dictators list, Mugabe is universally accused of using anti-imperialist and anti-racist propaganda to divert attention from his own oppressive policies, blaming the west for African problems. How-ever, few people in Europe understand the underlying features of these problems.

When the Marxist Zanu party finally succeeded in ousting British imperialist rule from Zimbabwe in 1980, Mugabe became the symbol of a new progressive African leadership and was copiously rewarded with honorary degrees by many western universities.

One would be inclined to consider such western largess unusual for a Marxist leader in the middle of the Cold War, but that’s because Mugabe was forced to compromise his revolutionary principles in the interests of ‘realpolitik’. The best one could hope for when dealing with a rapacious British imperial state was a meagre share for Zimbabweans of their own national resources, or nothing.

When the Lancaster Agree-ment was signed in 1979, Mugabe agreed to allow a 20-seat representation for the white minority and a 20-year moratorium on constitutional amendments. This was bad news for the landless peasants, hungry for land redistribution, who made up the majority of the population.

Nevertheless, Mugabe’s progressive policies in the areas of health and education produced remarkable results. From 1980 to 1990 infant mortality rates had been significantly reduced, malnutrition rates halved and Zimbabwe had one of the highest literacy rates in the developing world.

One of the problems in understanding the internal politics of Zimbabwe revolves around the conflicting interests of the rural landless peasants (what we in Ireland used to call ‘spalpíní’) and the urban working and middle classes.

Torn between the competing interests of these classes, his own desire to stay in power, and the voracious drive of multi-national companies to exploit the resources of his country for their own gain, Mugabe tended to vacillate in a vortex of competing demands.

If he ignored the interests of the imperial powers, they would put measures in place to ruin his economy or even assassinate him, as in the case of leaders like Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana who made the mistake of putting their own country’s interests first. On the other hand, he also had to appease the desires of Zimbabweans.

When the World Bank forced ‘structural reforms’ on the Zimbabwean economy in 1991, unemployment soared, and Mugabe lost the traditional support he had enjoyed among the state sector workers and the middle classes.

Along with the minority Ndebele (who were strong in the trade unions) and politicians spouting what Mahmood Mamdani described as an “uncompromising” free-market ideology, they formed the basis of an emerging opposition movement, steered by influence from the US Ford Foundation, the Heritage Foundation and others in the direction of neo-liberalism.

Meanwhile, Mugabe was facing fierce pressure from his landless ‘veterans’ who called for radical land distribution. After losing a 2000 referendum on the issue, the peasants rebelled and invaded the white-run farms.

Due to Mugabe’s support for this land revolution, the US imposed severe economic sanctions on the country. All credit from international financial institutions and multilateral development banks was cut off. Although Zimbabwe continued to trade with African and Asian countries, there can be no denying the severity of these sanctions on an underdeveloped country.

But there were other reasons motivating the west’s desire to oust Mugabe. He had defended the DR Congo against the Anglo-American-funded proxy armies of Uganda and Rwanda in 1998. The imperial powers had used the Ugandan and Rwandan armies to plunder Congolese minerals – this is one of the many ‘little secrets’ of recent African history.

Another reason they wanted Mugabe out is because he refused IMF ‘conditionalities’. The Heritage Foundation cited his insistence on subsidies for agriculture and state-owned industries, customs and tariffs on imports and land redistribution as the chief cause of concern.

There is therefore a clearly inconvenient truth in Mugabe’s anti-imperialist rhetoric. That is why Mugabe is Africa’s Hitler, and the dozens of other dictators the imperial powers support are not.