Dublin businessman Ohan Yergainharsian is founder of the well-known Sona Nutrition Company. He talks to Catherine Reilly about his Armenian heritage, and how his family survived the genocide that took like lives of so many

Ohan Yergainharsian is on holidays, but the Dublin entrepreneur’s eagerness to speak about his Armenian roots means that Metro Éireann’s telephone call – to faraway Dubai – is answered immediately.

Armenia’s diaspora is proportionally massive, with estimates putting it at around eight million (to Armenia’s population of three million), and Ohan Yergainharsian was among those who grew up outside the present-day borders of his motherland.

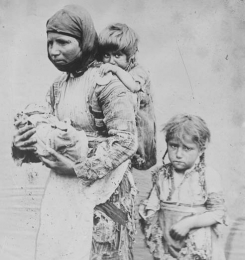

His family history is laced with trauma, but ultimately is a tale of survival.

“My grandparents were people who managed to escape the genocide during the First World War in Armenia,” reveals Yergainharsian, in reference to the brutal onslaught on the Armenian people by the Ottoman authorities, which is thought to have claimed the lives of one-and-a-half million Armenians. “That’s why you’ll find that the Armenian diaspora are mostly, if not completely, the descendents of those who managed to escape.”

Yergainharsian’s grandparents fled on foot, and his grandmother would later recall a 12,000-mile desert trek.

“My mother, for example, was born in a desert town in Jordan,” says Yergainharsian, “and I was born in Jerusalem. When I was growing up there were 300,000 Armenians in Lebanon, there were 600,000 Armenians in Iran, and maybe 250,000 Armenians in Syria.”

Yergainharsian – who later attended university in Lebanon – was always surrounded by ethnic Armenians, and the concentrated populations of Armenians in the diaspora ensured that the cultural and linguistic heritage wasn’t easily forgotten.

“You’ll find that they’d congregate together, build up schools, churches, organise sporting activities which kept the community together, so it was easier to maintain the cultural and linguistic links with your roots,” he remembers.

His first holiday on his own as a 17-year-old was to Armenia, where he still has family. “In fact, I have relatives who immigrated to Armenia from the diaspora,” he adds.

Yergainharsian married an Irish woman in 1977, and they settled in Ireland permanently in 1983. His Armenian family thought he was mad for moving to a recession-hit Ireland (“They were telling me ‘You are crazy, the VAT in Ireland is 35 per cent!’”) but he stuck it out and established Sona, which today is a highly successful company producing nutritional supplements and herbal remedies.

And Yergainharsian seems genuinely modest about his business success. “I think in some ways it was partly to do with hard work but also partly to do with the fact that over the past 25 years the Irish economy has – it’s the old story of the tide lifting all boats – it has benefited me the same as everyone else. Hard work is always compensated by opportunities, even in the middle of recessions.”

Despite his strong ties to Ireland, Yergainharsian still maintains close links with Armenia, and his last visit was in December.

“I think Armenia is suffering just like everyone else in this global economic crisis. It is impacted a bit less on account of not being in the mainstream economy – this has shielded it a bit from the ravages of the global downturn,” he comments. “But still, it is coming out of a collapsed Soviet system, war, a blockade, an earthquake. People who suffered during the earthquake became homeless, and some of them still are 20 years later.

“The economy in Armenia is very slow, very limited, very poor, and it’s trying to cope with issues,” he continues. “Remitt-ances are very important to Armenia, and remittances have dried up, and that’s probably the biggest result that Armenia is experiencing in terms of the global downturn.

“But I think in some ways, it reminds me of the old adage that ‘those who expect nothing shall not be disappointed’. There’s a bit of an acceptance that Armenia was already poor and it couldn’t get any worse on the part of some of the Armenians over there.”

Nevertheless, Yergainharsian believes that significant investment prospects do exist in Armenia.

“I think there are huge investment opportunities in Armenia... the resource that it has is the very highly educated population, and also the area geographically that it’s in, in that within a couple of hundred miles there are probably 60 million people who would benefit from what Armenia can do: Armenia would not only be serving its own local market but also the neighbouring markets.”

Armenians are hard-working, individualistic (“Bring two Armenians together and they’ll have three political parties established,” jokes Yergainharsian), family-orientated and outward-looking. “We are very, proud of our Christian heritage and yet in a social sense as opposed to a religious sense,” he adds. “We are very tenaciously clinging to our heritage, we see it as something worth preserving, and that is something that has sustained Armenians for the past 3.000 years.”

He believes Armenians’ history of occupation has impacted on their very selves: “It’s shaped our characters. When you are always forced to change, you cling to what you know or what you are a bit more, you fight for it a bit harder,” he says.

In Ireland, too, Yergainharsian has been involved in efforts to keep the Armenian language and culture alive among the small population of Armenians, numbering around 100 individuals. One idea in the pipeline is a Sunday school. “We’ve managed to get eight kids but they range in age from five to 12.”

Many Armenians in Ireland are Armenian by descent, rather than through nationality, and grew up in other former Soviet countries. As a result, the proposed school would play a key role in sustaining the Armenian language among their children.